A Case for Gift Planning Early in Donors’ Cycle of Generosity

Wm. David Smith, CAP®

Published: 07/14/2021

Healthcare fundraising professionals frequently asked themselves: How can we secure more blended gifts to advance our mission? This question is especially relevant since planned giving in the healthcare subsector is less mature than in higher education. The need for current gifts to healthcare institutions clouds the vision for and execution of an effective planned giving program since deferred gifts may not be realized for eight to ten years hence.

As trailing and leading baby boomers reach their late fifties and mid-seventies, respectively, a golden opportunity exists for gift planning (1). The baby boomer generation’s total wealth exceeds $64 trillion (2). Since 40% of boomers are retired, (3) the inter-generational transfer of their wealth is currently underway (4). While donors in their fifties and sixties typically have needs and goals that differ from older donors, gift planning offers solutions for all.

An evolution in gift planning

Bequests in a will or trust were front and center of all planned giving programs for decades and continue to be a priority. However, the Tax Reform Act of 1969 ushered in new definitions, requirements, and tax benefits for what are known as “split interest” gifts. These new gifts included charitable remainder trusts, charitable lead trusts, pooled income funds, and remainder interests in personal residences and farms (5).

The planned giving landscape has changed significantly since 1969. The fundraising vernacular to describe these programs has evolved from deferred giving, to planned giving, and now the commonly preferred term is gift planning. This change is much more than mere semantics but reflects the growth and sophistication of when and how more mature fundraising programs engage in gift planning discussions with prospects.

Influences in the evolution of gift planning

Three important factors influenced this evolution in the gift planning space:

- the significant increase in wealth in the US over the past two decades

- an increased recognition that gift planning vehicles can address donors’ needs caused by greater wealth

- donors’ desire to make a significant impact on organizations most important to them during life rather than only at death.

Let’s consider these three factors in more detail.

Increase in wealth. According to the Federal Reserve, the average US household net worth in 2019 was $746,821.05 compared to $189,367.92 in 1989(6). For the top one, five, and ten percent households, net worth increases were equal to or more significant than the general population, as noted in Tables 1-3.

Simply put, the average household net worth increased 3.70 to 4.80 times over the past twenty-year period. These data points are important when one considers, according to U.S. Trust, that 90% of high net worth households (an annual household income greater than $200,000 and/or net worth greater than $1,000,000, excluding primary residence) reported making charitable donations compared to 56% of the general population (7). This study found that high net worth donors gave $29,269 to charity in 2017 compared to the general population that donated $2,514 to charity the same year. High net worth individuals and couples comprise the majority of healthcare organizations’ major and principal gift donors based on Heaton Smith’s work since 2009. The significant increase in wealth alone creates meaningful gift planning opportunities for the healthcare sub-sector.

Increased interest in gift planning. A material increase in wealth is often accompanied by more complex donor needs and goals that gift planning may help address. Needs and goals include writing a will, updating an existing estate plan, how and when to make gifts of assets rather than gifts of cash, tax planning, long-term income needs/goals, inter-generational wealth transfer decisions, and strategies for leaving a legacy for a healthcare organization and other not-for-profit institutions. For some higher-capacity donors, their needs and goals involve more than making a major, principal, or campaign gift to a healthcare organization. Solutions to donor needs and goals do not necessarily have to be complex, but sometimes complex needs and goals require more than simple solutions. The Giving USA Foundation "Leaving a Legacy" report found that 19% of respondents reported funding a current charitable trust (no testamentary charitable trusts were reported) (8). Charitable trusts can uniquely meet donors’ income, intergenerational wealth transfer, tax reduction, and philanthropic goals. The report also found that donors who funded charitable trusts had a net worth of $10,000,000 or greater, and they funded charitable trusts only after consideration of less complex gift options. This highlights the reality that for many higher capacity donors, a simple bequest does not solve their needs or meet their personal, family, or philanthropic goals.

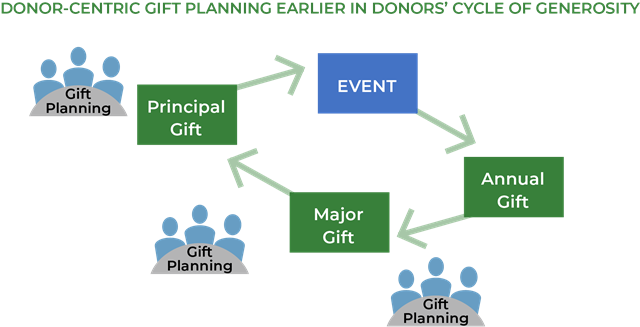

Maximizing personal philanthropy. Most donors with whom my colleagues and I work want to help their healthcare organization “all they can, when they can.” These high affinity, high-capacity donors want to make a significant impact on healthcare organizations during life as well as at death. However, few donors understand the benefits and effects of gift planning on their estate, their heirs, and their healthcare organization. They are busy “living life” by working, traveling, caring for family members, and volunteering. It is a gift planning officer’s responsibility to spend the requisite amount of time with donors to understand their needs and to offer relevant solutions at the time of need rather than waiting until donors are in their 70s or 80s. How should the three aforementioned factors shape a healthcare organization’s gift planning program? Consider introducing donor-centric gift planning earlier in a donor’s cycle of generosity. Even donors in their 40s or 50s, depending on their fact pattern, may be interested in long-term gift planning. The following illustrates an outcome of this strategy.

A case study: Prisma Health Upstate

Prisma Health Upstate, located in Greenville, South Carolina, is part of Prisma Health, includes an academic medical center, and is the largest health system in the state. The Office of Philanthropy leadership made a decision to introduce donor-centric gift planning earlier in their high-affinity, higher-capacity donors’ cycle of generosity. The results are interesting and instructive.

Table 4 lists the ages of donors who were engaged in gift planning conversations and the percentages of each age category. Note that 66% of donors were in their 50s and 60s. These are high-affinity, higher-capacity donors and include those with significant volunteer histories.

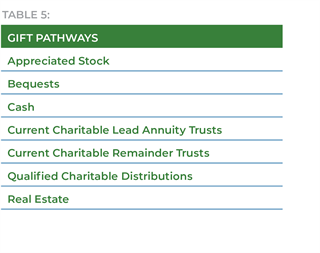

Hard data for the average-sized planned gift in the US is difficult to source, but a recent report on bequests is useful. “Everyday” donors in the study included an average bequest of $78,630 in their estate plans. However, Prisma Health Upstate’s average planned gift is $928,000, which is nearly twelve times the national average. Gifts used to calculate the institution’s average are documented and include gift agreements based on the impact and legacies these donors want to leave. Importantly, these gifts, listed in Table 5, include a mix of vehicles, and all but two gift pathways help the healthcare system now.

|

|

Donors in this cohort funded full and partial scholarships at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, programs and endowments for Prisma Health Upstate Children’s Hospital, programs for the Cancer Institute, neuroscience, and a camp for children with cancer, to name a few. They are current business owners, practicing and retired physicians, a former Fortune 500 CEO, senior health system executives, investment advisors, insurance professionals, and long-term current and retired employees of corporations—not dissimilar to donors in any gift officer’s portfolio. However, very few of these donors are truly wealthy by US standards yet were able to make meaningful gifts as young as age 51.

What needs and goals did philanthropy solve and meet for donors in this cohort?

• Establish an endowment

• Estate planning update

• Estate tax reduction

• Honor spouse through philanthropy

• Leave a legacy

• Long-term income

• Make the greatest impact on those served by Prisma Health Upstate

• Meaningful impact on healthcare organization while retaining control of most assets during life

• Reduce size of estate

• See fruits of generosity during life

• Meet scholarship recipients during life

• Tax savings–income and capital gains

Relationship-based fundraising

A key to introducing gift planning to donors earlier in their cycle of generosity is relationship based fundraising. Gift officers re-orient donor discussions from institution-focused to donor focused while articulating the compelling needs of one’s healthcare organization. The purpose of most donor meetings is to build trusting relationships and to fully understand their needs and goals that may include:

• Did their youngest child recently marry?

• Was their first grandchild recently born?

• For childless donors, how do they wish to leave a legacy?

• Are they approaching retirement?

• Are they expecting or did they recently experience a liquidity event?

• Have they recently received an inheritance?

• Do they have tax liability concerns?

• Would they like their giving to be more strategic and measure their gifts’ impact?

• Are they interested in endowment? • Would they like to experience the joy of meeting scholarship recipients?

• Do they want to share in the responsibility of their healthcare organization meeting the needs of more people in the community?

• Do they want to leave a significant and lasting legacy with a healthcare organization?

• Is your healthcare organization one of their three top charities?

While this is not a complete list, it is a good start to better understand the fact pattern of a donor for whom gift planning discussions earlier in their cycle of generosity may be appropriate. The youngest and oldest Prisma Health Upstate donors in its gift planning cohort, aged 51 and 82, funded current charitable lead annuity trusts. The younger donor had needs that differed greatly from the older donor. Yet, gift planning solved each of their problems with a similar gift vehicle: the younger a grantor charitable lead annuity trust and the older a non-grantor charitable lead annuity trust. If not for the introduction of gift planning earlier in the younger donor’s cycle of generosity, then this gift would likely not have come to fruition until a much later life stage.

Russell N. James III, in a paper entitled American Charitable Bequest Demographics (1992- 2012), found that donors who add a charitable beneficiary to their estate plans late in life “are of a smaller size than the longer-term planned gifts” (10). Prisma Health Upstate’s Office of Philanthropy leadership could have continued their previous major and principal gifts’ strategy with high-affinity, higher-capacity donors in their 50s and 60s and thus postponed the gift planning discussions until later in life. Many of these donors would likely have named Prisma Health Upstate as a charitable beneficiary in their estate plans due to their affinity for the health system. Moreover, a small percentage of those estate gifts may have been significant, but many would have been average-sized bequests rather than an average gift of more than $900,000. Such a strategy would have neglected the current needs and goals of younger donors, including their philanthropic goals.

Two-thirds of this donor cohort should have two-three more decades of continued engagement with Prisma Health Upstate but at a much deeper level. Moreover, they get to experience the joy of seeing the fruits of their generosity during their life. Perhaps most importantly, these donors benefited from thoughtful donor-centric gift planning earlier in their cycle of generosity that allowed them to give “all they can, when they can.”

1 (2018). The Transfer of Wealth, Welcome to the Windfall Years, 04-13. The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

2 Federal Reserve. (2021). “Q4, Distribution of Wealth, Distribution of Household Wealth Since 1989.”

3 Fry, Richard. (2020). “The pace of Boomer retirement has accelerated in the past year.”

4 (2018). The Transfer of Wealth, Welcome to the Windfall

5 Sharpe Group. (2008). “Was Planned Giving Invented in 1969?”. Sharpe Insights.

6 Federal Reserve. (2020). “Survey of Consumer Finances. Assets by All Families.”

7 Bank of America. (2018). “The 2018 U.S. Trust Study of High Net Worth Philanthropy.”

8 Giving USA Foundation. (2019). “Giving USA Special Report: Leaving a Legacy,” p. 19 and 41. Giving USA Foundation.

9 Stiffman, Eden. (2019). “Survey of Wills Created by Everyday Donors Shows an Average Bequest of $78,630,” The Chronical of Philanthropy.

10 Russell N. James III, (2013). “American Charitable Bequest Demographics (1992-2012).”

11 Russell N. James III. (2020). “The Emerging Potential of Longitudinal Empirical Research in Estate Planning: Examples from Charitable Bequests.”